Mapping the personal-collective memory with Samanta Batra Mehta

Samanta Batra Mehta finds a sense of permanence in the ephemeral. Contemplating on, often reimagining, her family’s generational migratory history, the inter-disciplinary Indian artist creates multi-layered pieces that mirror a state of being in a flux. Batra Mehta who was born in Delhi and grew up in Mumbai spent the first few years of her life on a ship. Now, it’s been over a decade since she’s made New York her home. An “incorrigible collector”, she will often use found objects that come with their own embedded histories and that reflect her preoccupations at the time of acquisition. She juxtaposes these evocative objects with her own ink-based drawings.

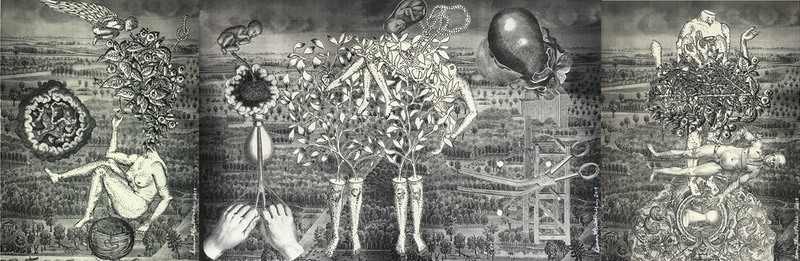

Batra Mehta tells me that when she shifted to New York in her late 20s, she began to look at the notions of identity, home, belonging, nation and land through an entirely different lens. “The highly political atmosphere in the US during that time and being a foreigner in a racially-aware land made me learn and unlearn so much. I travelled through nostalgia, memory, displacement, dislocation, migration, and these notions inevitably made their way into my art practice,” she says. Do artists create for themselves? Can art be a reflection of the sub-conscious of all and sundry? In the case of Batra Mehta, art holds within itself the power to be a salve for both the artist and the viewer. To understand the intention behind any of her works is to get under the very skin of this artist. And yet, her body of work resonates with viewers across borders — a sense of nostalgia is evoked, misplaced memories surface, an urgency for deeper inquiry is provoked. Batra Mehta’s work has been showcased at galleries across the world, from New York to Hong Kong, and at some of the world’s leading art fairs. Some of her newer works are on show through August 10 at TARQ (Mumbai) in a group show titled ‘Osmosis’ curated by Shaleen Wadhwana. We attempt to unravel the intricacies of this artist’s work and the myriad interpretations they hold. Excerpts from the interview… Design Pataki: History and memories find form in your work. How and when did your interest in using objects from the past emerge in your work? Samanta Batra Mehta: The work ‘Twilight of the Gods’ and the ‘Memory Box’ series are an intersection between childhood memory, personal and political history. My maternal grandparents lived in a rambling home in New Delhi, which they built after the Partition. In the aftermath of the Partition, my grandparents, like millions of Indians, arrived in Delhi as refugees having left their homes and material belongings behind. As a child, I used to love visiting that home in Delhi where my mother grew up. The rooms were filled with stories of the past. In one of the many rooms radiating from a central courtyard stood a glass-fronted almirah which was filled with a collection of objects and curiosities that stood testament to the journeys and memories made. In my work, I have used sections of original antiquarian maps and engravings of British India, collaged text and imagery from antiquarian books on contemporary printed material, and vintage medicinal and laboratory glass containers to re-create this cabinet of curiosities. The work also serves as a memento mori of our tumultuous family history. The title ‘Twilight of the Gods” is the name of an opera written in 1876 by German composer Richard Wagner and is a translation of a prophesized mythological war of the gods which causes the end of the world. DP: What are the kind of objects we might we find in your possession? SBM: Growing up there was a lot of exposure to art, books, travel. My parents collected antique maps, prints and glass and porcelain art. I have always loved and collected books. I bought a small painting with my first paycheck as a management trainee at a bank. Soon after, not only contemporary works found me, but also antique objects, prints, maps, engravings etc. (I have a nice little collection of contemporary art). A few years after I had moved to New York, I realized these collected (antiquarian) objects collectively told a story. Apart from their own embedded histories and visuality, they reflected preoccupations of mine at that particular time. I decided to use some of my collection of antiquation books, engravings and maps, interspersed with my own drawings to make art-works. A whole new dimension opened up. Each object I collect brings its own story which I re-imagine in my work. DP: Nature has a strong presence in your work, as does the human body. What are some of your intentions behind the fluid use of these motifs? SBM: Nature/land/landscape is seen as a metaphor for the body (and vice-versa) and as a site for germination, nourishment, degradation, trespass, plunder, colonization and transgression. These tensions and symbioses of land/body/people and the hegemonic structures that seek to control them are explored in my work. My artwork is a commentary on the human condition and the environment we inhabit. Themes in identity, personal history, gender constructs, socio-political order are debated in my layered artworks comprising drawing, collected objects/installation and photography with a visual vocabulary that includes the human form intertwined with that of nature. Nature/land/migration also appear in my artistic re-imaginings of family history. My grandfather was a botanist and college professor during the Partition. Later, as an agricultural scientist, he developed drought-resistant rice for the newly independent India. In my art, I evoke the extensive gardens in Northern India he painstakingly created, along-with his stories of the lands and homes my grandparents lost during the Partition. These fantastical gardens conjured by my families’ collective imagination, the larger political debates underpinning them also appear in my work in the form of nature. DP: Tell us more about the process and thought behind Voices of my Silence. SBM: Voices of My Silence is a work made from three wooden antique radios, onto which acid-free paper hand-cut printed drawings have been découpaged. After my children were born, another dimension opened up in my work. With family spread over three continents, we embraced the machinations of being a global family. Building a home, raising a young family re-creating traditions and acquiring new ones in my new home country were all things that crept into my work. I reflect on how these new meanings are created, how lines are re-drawn in different cultural, social and geographical settings. I reflect on my own experiences of migration, family and tradition in the age of hyper-connectedness and shifting loci. ‘‘The Voices of My Silence’ speaks of these reflections.