Interviewing Brazilian Architect Marcio Kogan Of Studio mk27 On Modernism, Luxury Ecotourism, And Hospitality Design

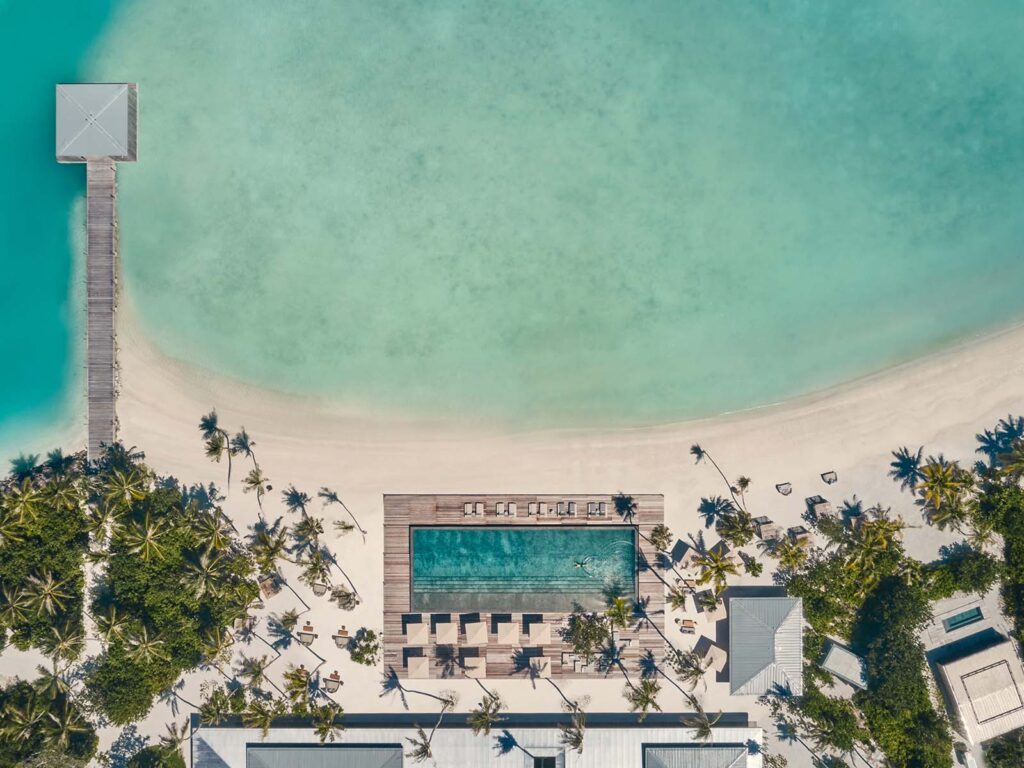

When Marcio Kogan was in architecture school, he hated Brazilian modernism. For those acquainted with his work, this could come as quite a surprise; Kogan’s architectural practice of well over forty years, studio mk27, has forged a compelling legacy of rethinking and giving continuity to the Brazilian modernist movement. An essence of utmost perfection with comforting naturalistic overtones, a dramatic interplay of light and shadow, and an immense value on formal simplicity shine through every one of their projects. We were first introduced to the brilliant architect through his design for Patina Maldives, a luxury resort that stands as a radical example of biophilic design. The architecture of Patina Maldives takes clear inspiration from the beauty and metaphorical significance of the island landscape. In order to not break the visual beauty of the horizon, his vision focused on delicate architectural lines that remain respectfully low, open public spaces that are light and inviting, and an overarching ethos of coastal glamour. The more attention we paid to the nuances in the design of the island hotel, the more impressed we grew with the architect’s creative sensibilities.

Kogan’s ideas of luxury, sustainable hospitality, and conscious living are in clear alignment with the new wave of ecotourism that is slowly but surely growing more popular with educated consumers. Interestingly, another prominent influence on Kogan’s creative sensibilities is cinema; his early career was split between film and architecture, and the former continues to inform the latter. We spoke to Kogan about his relationship with Brazilian modernism, view of sustainable luxury, and history with Indian design –

Can you give us an insight into how Brazilian modernism informs your creative process? Are there any particular features of Brazilian modernism that you incorporate into your projects outside Brazil as well?

When I was at architecture school, I hated Brazilian modernism. At the time, the teachers pushed us to follow the movement in a doctrinal way and I was much more interested in what was happening in the international scene: as Centre Pompidou, Archigram, and several utopists.

A few years later I began to understand the power of our modernist architecture. Not only by Oscar Niemeyer, but by several other architects like Lucio Costa, Affonso Eduardo Reidy, Burle Marx, Villanova Artigas, João Filgueiras Lima, Rino Levi… Later joined by Lina Bo Bardi and Paulo Mendes da Rocha. More and more, I started to deeply admire this movement in Brazil, and studio mk27’s architecture was

increasingly influenced by it, obviously re-thinking it in a contemporary way; from its elegant sobriety to the intense integration between interiors and exteriors.

I especially appreciate this strong integration between the interior and the exterior. In numerous projects, the windows are recessed into the walls, making the space 100% fluid. There is a constant search for enlargement of spaces. This favors all passive solutions for climatic comfort in warm climates as it usually leads to spaces with crossed ventilation, envelopes with different layers to provide filters and shadows when the afternoon sun hits.

While building in beautiful places such as the Maldives or the Brazilian beaches and countryside, all architecture can do is let nature speak louder.

Height is an interesting motif across your work; given that your projects rarely rise above the horizon and aren’t more than one storey tall. Could you tell us why this is?

Actually, it’s not only about height, but proportions. I have a strong influence from my former career as a filmmaker: the love for the wide-screen proportion and the way that the viewfinder frames elongated views. Also, the horizontality commonly explored in studio mk27’s projects reflects our respectful approach to the surroundings. While building in beautiful places such as the Maldives or the Brazilian beaches and countryside, all architecture can do is let nature speak louder.

Are there any new materials or processes that you have been experimenting with?

In my first projects, I would always use white, pure surfaces to reinforce the shadows and the simple volumes. The projects had a futuristic touch, antiseptic. Then, one day, a client introduced himself saying that he liked my work but that he did not want a white house. That awakened in me an interest for textures and the exploration for the materials used in the projects. I gave him a house with a lot of wood, rustic stones and the result was quite happy, and the house is beautiful with a pleasant and cozy atmosphere. Since then, the projects of studio mk27 have never been the same. Even when we seek to do something more industrial or more aggressive, with the use of metal plates or a profusion of bare concrete, we try to add other layers of material treatment, the concrete has the print of the wooden frame, the metal sheets are waved or perforated with floral motifs and so forth. It is what I like to think of as the tactile dimension of architecture, something closer to the human body.

In our latest projects, we’ve explored the use of the “biribinhas” (rustic eucalyptus poles) that filter the light in a magical way.

Your recent project ‘Patina Maldives’ has garnered rave reviews. What has been your experience working on this project?

For studio mk27 it was a great learning experience. We designed everything on the island alongside various collaborators. We don’t always have this kind of opportunity. A client that, led by Evan Kwee, elegantly respected the work of the entire team. It was a great experience and surely our expertise in hospitality is already influencing many of our projects. A privilege!

According to you, what are some of the most distinct ways in which you’ve managed to merge luxury with sustainable architecture in your hospitality projects?

Luxury is no longer a tangible thing. Consumers expect upscale hotel brands to provide a positive contribution to their environment and social ecosystems, being responsible, ethical, and sustainable. Patina Maldives island is self-sustaining and the uniquely attentive and cordial service is due to the training of the local population. Guests are knowledgeable and conscious of the meaning and experience attached to luxury.

The key is to be authentic, it’s mostly getting back to essentials. In the Maldives, sand, skies and ocean, all architecture can do is humbly filter the lights, frame the views, creating different narratives as one strolls around the magnificent surroundings. We were able to produce architecture that is much less important than nature. Contemporary, classic and elegant.

In your opinion, what does the future of luxury ecotourism look like?

We see a growing attention to the connection with the place and culture, the importance of uniqueness and authenticity. The special role of wellness, places to exercise and meditate, a generous bathing room with a view. And due to the pandemic, of course, the need for open air spaces, a deep integration of inside-out, spaces that are welcoming and poetic, rather than sculptures. I see a search for diversity, for empathy with the other and our environment, the need for quiet solutions to our problems.

How is working on a hospitality project different from working on a residential or commercial project?

My strong link with the movies since my days as a student at the university created a spontaneous work process for me. I always create a character that is going to live or use the space in question. He has a life story and is constantly moving through the project. For the past few years we have been so many of them, designing from master plan to the handles…One day we are enjoying loneliness and watching birds migrate. At the other we are barefoot trancing on the beach club or making love long before dawn. At times we are surrounded with noisy kids wearing scuba diving masks. All in all, we seek for complicity.

Is there anything about Indian architecture that has influenced your work? What would your dream project in India look like?

A few years ago we worked on a house project in Delhi and it was a very nice experience. I began my research on Indian culture through the culinary (I love to eat). During my visit to India I had intensive classes of Vastu Shastra where I received my first teachings of design according to the complex norms of traditional Indian architecture. Upon returning to Brazil I invited an architect friend, a professor at the University of Brasilia, who is a specialist on Indian architecture, to give a course that would broach on topics from Fatehpur Sikri to current days for all of studio mk27! It was very cool!

The project rigorously respected all principles of Vastu Shastra, from its placement on the site to the orientation of spaces establishing harmony between the natural and supernatural forces. I liked it! At the entrance, surrounded by water, a small temple already indicated a good start. We used a multitude of different textures, materials and shapes in an attempt to create a playful game of light and shadow throughout the project. Unfortunately, the house was not built.