Indian Artists From The Diaspora Reflect On Identity, Expression And Connections With Their Homeland

- 25 Jan '21

- 4:52 pm by Beverly Pereira

Photography Credit: Courtesy of Sahana Ramakrishnan

Some arrived on a ship over half a decade ago; others, by air in recent years. Many had been uprooted from a country torn apart by violence, while others crossed borders with the simple hope of a new beginning. Still many others are making the journey as we speak — a journey to a destination far removed from their own. Historically, countless Indians have found themselves arriving on new shores. In 2019, according to an estimate released by the UN, the Indian diaspora was the largest in the world at 17.5 million.

What, then, does it mean to be culturally hybrid? And, how does one grapple with the complexities of a diasporic identity while straddling geographies, cultures, memories and even opinions? Can that much-sought-after sense of belonging ever set in? Even if and when it does, what are the challenges faced in the journey towards assimilation of identity?

We speak to two Indian artists living abroad whose work speaks to contemporary culture. Their art expresses global themes, perspectives and issues, even as their voice carries notes from the motherland and intergenerational ideas from the East at large.

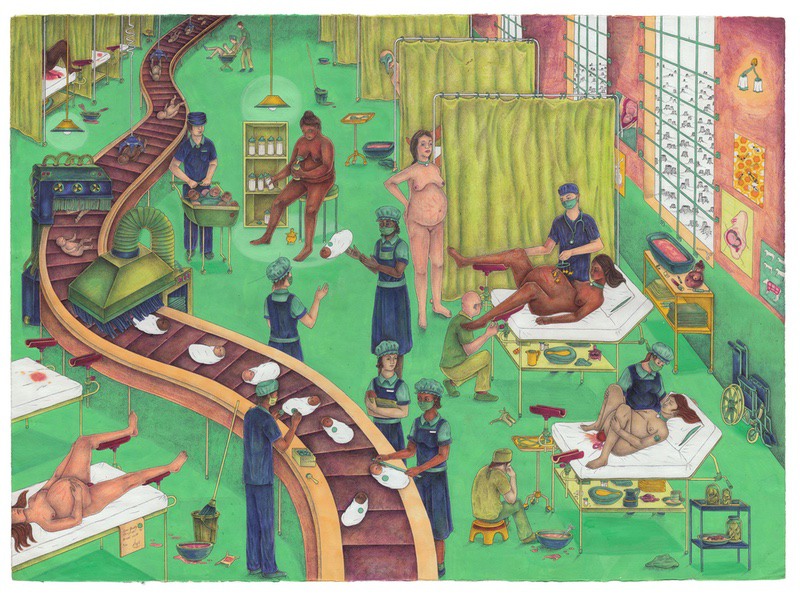

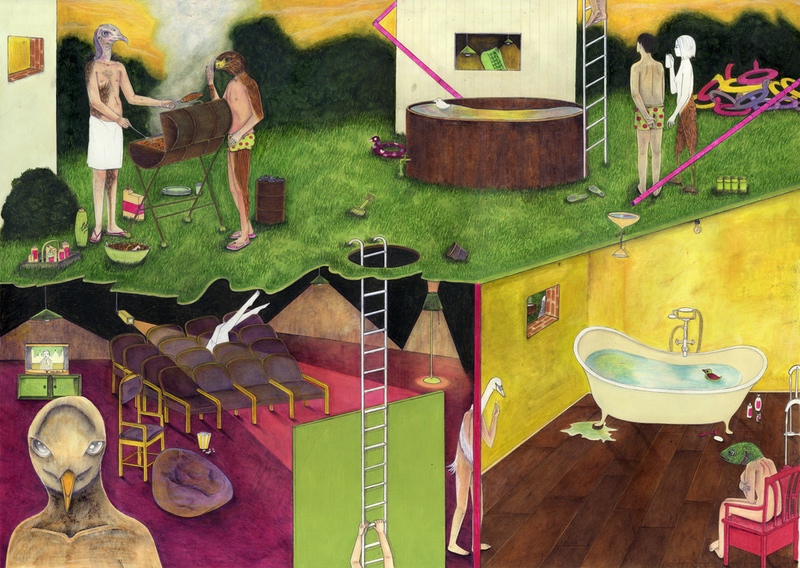

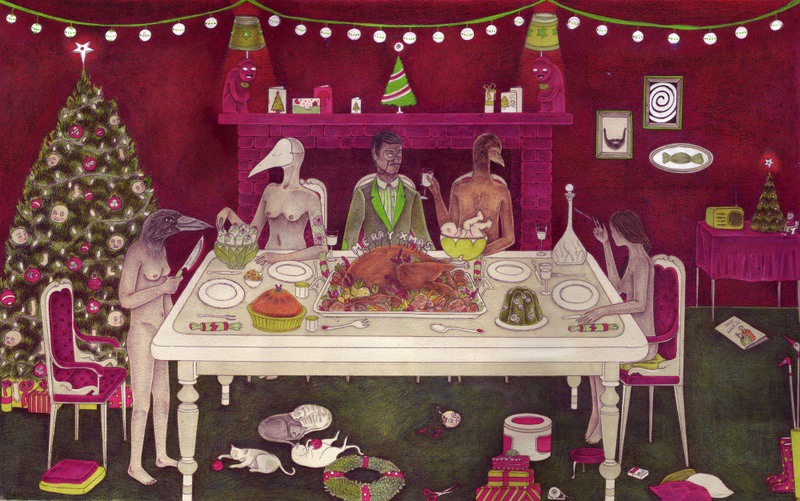

Janine Shroff –

Janine Shroff’s art reflects themes like gender, relationships, population, and even pregnancy. The queer designer and illustrator was born in Mumbai and lived in the city till she was 18, after which she moved to London to study and work. Her body of work portrays androgynous figures — birds and humans — engaged in the quotidian in a strangely surreal yet all too relatable landscape. Her illustrations and sketches have a touch of humour tinged with the macabre and pose a solid narrative, a commentary, if you will. Shroff is also member of the Kadak Collective, a collective of South Asian visual storytellers, designers and zine makers.

Having lived in London for almost two decades, she says, “Mentally, one half of you lives in India and the other half in the UK. It took me a little while, about eight years, to feel at home. As an immigrant you may need to live in this half-in half-out hazy limbo for a long time.” She has been working with acrylic and watercolor pencils over the last few years and in the past used a ballpoint pen for grain and detail.

“I’d like to try more three-dimensional materials going forward — like embroidery and paint on wood,” says Shroff.

What were some of the influences that shaped you as an artist during your formative years?

Lots of comics, graphic novels, MAD magazine, Asterix and Amar Chitra Katha. I have always loved Mughal era miniatures and Persian miniatures, anything that had detail to make the viewer come closer to look at it.

What were and continue to be some of the challenges faced on the journey towards assimilation of identity and sense of belonging.

This idea of ‘straddling of cultures and geographies’ can be boiled down to its simplest and most prosaic form: The student visa and the work visa. This piece of paper and stamp will rule your life for at least ten years and is a weight both in the actual cost of all the paperwork and in the emotional cost of not knowing what your life will be like year to year. The prosaic nature of a visa shifts how you work, live and exist in a space. It defines so much of your life and yet can in an instant disappear. In general, you just need to jump so many hoops constantly. I cannot articulate how draining it can be, but I’m glad it’s over!

Why do you find yourself challenging the norm, addressing such themes as gender roles, feminism, sexual identity through the lens of the everyday.

Some of my themes like gender, relationships and population, pregnancy, etc have largely remained consistent over time. They spring from a sort of compulsive obsession with them. They are such vast topics that there is a lot of exploration within them and because they do form a part of our everyday life, it’s hard to escape thinking about them.

Androgynous figures and bird-like characters set in a modern dystopia have a strong presence in your work. Tell us more.

Androgyny and our current-day obsession with how gender is defined is something I’ve always been interested in. I enjoy creating strange but relatable worlds for these characters to live in. I’m currently re-drawing the tarot cards with my bird-characters and playing with the gender in them. It’s also been interesting to see what I want to include in each card or edit out as they are so rich in symbolism. But some of it feels distinctly outdated. For example, theer are lots of references to the church or Christianity in the older medieval decks and a hotchpotch of Egyptian, Alchemical and Hebrew symbols in the Rider-Waite deck, as mysticism was very popular at the time when the deck was made in 1909.

What are you working on at the moment?

I just finished two paintings; one that I began just before the pandemic and one that I finished just after it began. So they both reflect the 2020 apocalypse mood. I am also currently working on a set of bird people on tarot cards and a newer, larger series of works about the grotesqueness of the body (specifically breasts). I will also be participating in an upcoming group exhibition curated by Tatiana de Stempel and GALLERY46 in London in of February.

Photography Credit: Courtesy of the artist

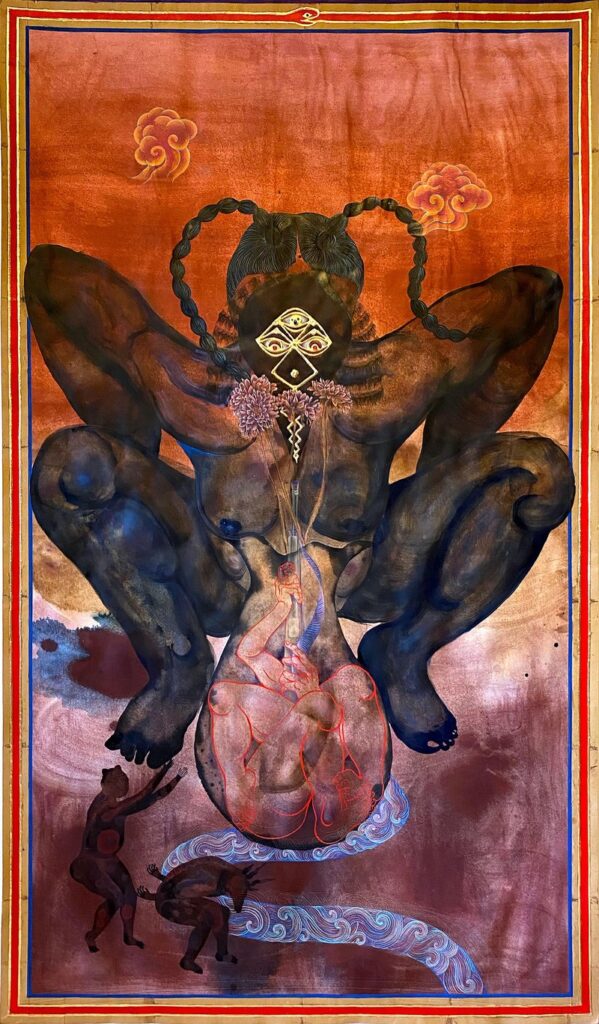

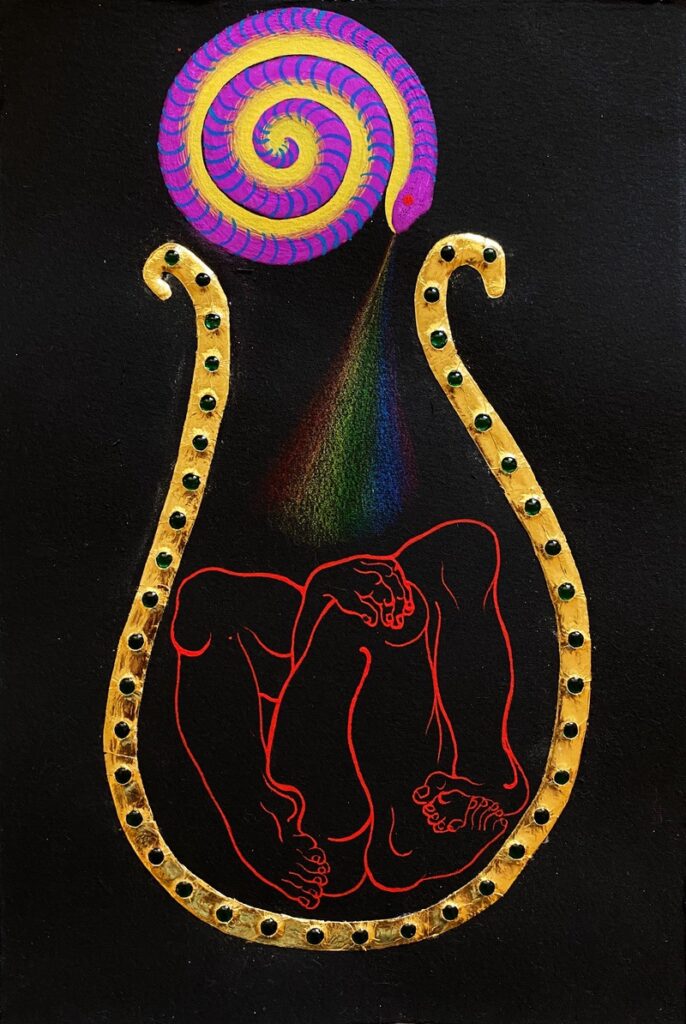

Sahana Ramakrishnan –

Animals like the buffalo, lion and black jaguar have a strong presence in Sahana Ramakrishnan’s art, which is greatly inspired by ideas and concepts from Buddhist, Hindu and Greek mythology. Her pieces can well be likened to a mix between tapestry, collage and scroll drawing. Ramakrishnan was born in Mumbai. She grew up in Singapore and has lived in Brooklyn for several years. “Because I was born and have always lived in cities, I see my life as an arching path of reconnection to nature, land, animals. At least I do now — since the pandemic hit I’ve had a lot of time to reflect on my relationship with where I live, what national boundaries and borders really mean,” she says. Ramakrishnan used to work in oil on canvas in college, but moved on to inks and egg tempera on paper as she experimented with the avenues of mixed media. Of late, she has begun to veer towards oils again.

“Oils can very forgiving in the sense that you can always change, take away, layer, add. You have control over so much. Right now, I like that more and I find it both challenging and exciting.”

You revisit mythological concepts across cultures in your pieces. How did your interest in these ideas from Hindu, Buddhist and Greek philosophies emerge?

My interest in Greek mythology probably comes from its morbidity and drama. I can’t pinpoint a specific time when that interest flourished because its remnants, iterations and archetypes are very visible throughout the modern culture that I grew up with and currently live in, hidden in the names of things, in the books we read and in the TV shows we watch. I feel that Greek Mythology, as with many myth cultures, is very much alive — though changed through the world it finds expression through and sometimes relegated to hide in the undercurrents of things.

I can pinpoint the exact time and place I became engrossed with Buddhist mythology, and by extension my interest in Hindu mythology. I was on a trip with a friend in Dharamshala. We had just finished a ten-day trek and ended up in the town to relax for a few days. We walked into a random store and I saw it — I don’t remember how long I was standing there staring at it, but I was absolutely silenced by it. It was a Thangka or painting of Mahakala, I found out later. I felt like an unsettling, urgent unresolved question inside me — one about my true nature — had been quenched. Not in a way I can explain in words, but staring at this wrathful, dancing, celebrating figure, in the midst of the chaotic maximalist environment made me finally feel that I had a place in this world. I suddenly felt I understood something inside me I hadn’t before, something that caused me to hate myself previously. Since then I have had so much respect for the wisdom of specifically Tibetan Buddhism, and certain aspects of Hindu Mythology. When it comes to mythology and religion, I trust myself to learn and take what I need and leave the parts that don’t apply to myself behind.

Photography Credit: Courtesy of Sahana Ramakrishnan

What is it about materiality that draws you to layer your pieces with found objects, materials like glass, gold leaf and fabric?

I’ve pared down the materials I allow into my work now. I think a lot of it comes from experimentation with different textures. I like to touch stuff. In a sense, I like my works to feel like objects. Texture can communicate something almost sensual, but it’s also so much more than that. In my works on paper though, I do tend also to use materials typically used in Tanjore painting. My Grandma does them really beautifully. So I learned a little bit of how to make them and adapted them for my own works.

You have spoken of a Nigerian writer who greatly impacted your practice. Tell us more.

His name is Amos Tutuola, and it was specifically a moment in his book, My Life in the Bush Of Ghosts, which is sort of a nightmarish, fantastical, folk tale narrative. He explores the idea of what happens to a mortal when he strays into the land of ghosts. The story in general is so visceral, brutal and sometimes quite disgusting and painful. I think I was reminded of the Buddhist idea of the fearful Bardo, and saw echoes of the wrathful, terrifying God I had seen in Tibetan Buddhist paintings. A necessary journey, where fear and gruesomeness come hand in hand with celebration, excitement and transcendence.

There was one moment in the book that caught me in particular. A young boy is trapped inside a pitcher like a pre-Incan mummy, with his neck surrealistically elongated so that his head peers over the top. Each night he is helpless as he is visited and harassed by terrifying animals and ghosts alike. I’m constantly searching for moments in literature and myth where common Western human-animal power dynamics and human relationships with the natural, physical world are capsized.

In what manner have geographies, cultures, opinions, experience and memory affected your practice?

Some of these reflections came about through my meditation on this vessel image, carried through from Tutuola’s moment in the pitcher. I reflected on the nature of a vessel — something that acts as a protective boundary, but by its very existence, as such, poses to potential for transgression, invasion, breaking, penetration. The vessel is a thing that comes with both protection and destruction in its wake, like sisters walking together. The vessel could be our body, could be our immune systems, could be national boundaries, could be our humanness. But most importantly, the line that the vessel draws between two spaces is a story that we tell ourselves. I am porous. I have no self except for what I have absorbed and accumulated from the generous world around me, throughout my lifetime, and what I continue to absorb and give away, intentionally or not. So where is the boundary?

Your work carries the weight (and expression) of diasporic identity as you explore perspectives on gender, sexuality, skin colour and other concerns that speak to the generation of today. Anything to share in this regard?

Yes – it’s that I don’t think a fight for gender and race equality can disregard the divide we’ve created in our minds about our humanness and the rest of the world that continues to make us, support us and love us. And vice versa — any fight for the climate and ecosystems that takes on a nationalist-fascist edge is abhorrent. They need to come hand in hand. Once you start to create a hierarchy of beings there is no end to it, it’s a slippery slope.

What are your working on at the moment?

I’m working on a new series of oil paintings. Outside of painting, I have been practicing Muay Thai for a few years. I am surrounded by professional fighters and friends who are dedicated to training and learning about fighting. A while back I had injured my wrist badly and couldn’t participate, so I’d sit in class and draw my friends sparring and fighting. Now it’s time a couple of works came out of that time period.