Identity Through Architecture – How Joya Mukerjee Logue’s Ancestral Home Shaped Her Artistic Practice

“My art would not exist without this house. Growing up within two cultures, I have been shaped by both my American family and my Indian family. The very foundation of my being is wrapped up in generations of ancestors before me, in their history, stories, experiences and their material memories that have been passed down. When I paint, I feel the connection to all of those before me, and I look to capture a story or a memory to embody my heritage. When I look to this house, I see that I am the sixth generation to walk this land and touch these bricks laid almost 200 years ago.”

Watercolour artist Joya Mukerjee Logue’s unique moniker ‘Rajovilla’ is a reference to what she believes is one of the most formative aspects of her identity and by extension, her work. Logue talks about her ancestral home in Ambala as though it is a living entity; a legacy personified; a distinct culture preserved in brick and plaster. Born to an Indian father and American mother, Logue’s upbringing straddled two worlds of cultural individuality. While she grew up in the U.S., her childhood visits to India were spent mostly at Rajo Villa. To her, the house and land are physical reminders of years past, and they serve as a backdrop to her artistic journey. Through Logue’s account of Rajo Villa’s historical and architectural background, we explore ideas of identity in relation to architecture, the preservation of legacies, and visual storytelling.

“A part of me would feel lost if we did not have our family home to welcome us when we arrive back in India,” she says. “This is not just a building, but rather a legacy. And as each generation leaves this earth, the home remains and is a symbolic embodiment of the collective history of my family.” Logue’s relationship with Rajo Villa isn’t uncommon – in an age of urbanization, ancestral homes all across the country serve as striking architectural representations of heritage and identity. They are special culminations of varied perspectives, with generation after generation leaving its mark with changes, additions and even detractions. These inherited mansions, havelis, and kothis offer a fascinating insight into regional architecture and the subtle differences that manifest in these spaces, even amongst neighbouring towns and villages. A strong sense of sentiment surrounds these structures, and the conversations around preservation and restoration grow increasingly relevant.

As it happens, Rajo Villa is presently listed as a built heritage site on the National Register of Monuments and Antiquities in Haryana, India. The house has been written about and referenced in architectural studies, historical accounts and even in literature. What made it particularly fascinating was not only its historical relevance but also its unique geographical position. Logue’s ancestors emigrated to Haryana from Calcutta, and as a consequence, built their home in an architectural style that was distinctly Bengali.

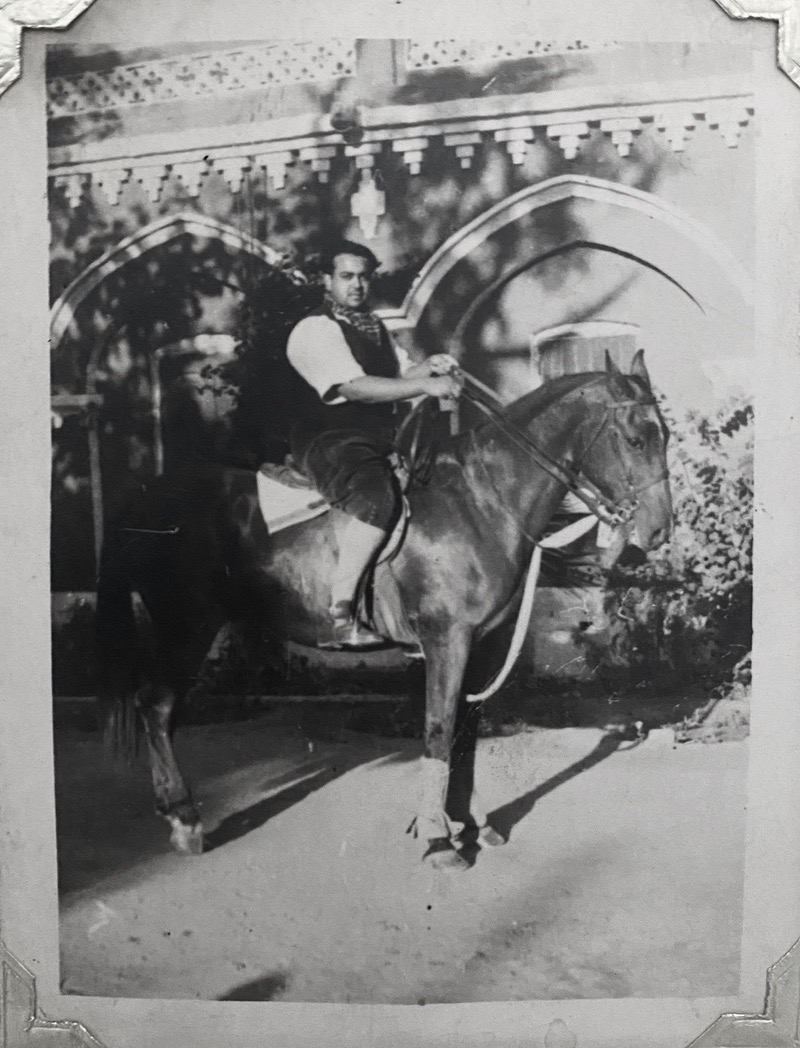

The Mukerjee’s of Ambala were a family of four generations of physicians who practised within the region for over 130 years. In 1845, Logue’s great great great grandfather, R.K. Mukerjee left Calcutta and travelled north by boat up the Ganges river to Grand Trunk Road, and eventually settled in Ambala. He opened a dawakhana and built a traditional Bengali single-storey bungalow in a circular shape, with brick arches wrapping around the home that opened to verandahs on every side. Eventually, the bungalow was named Rajo Villa.

K.K. Mukerjee, the son of R.K. Mukerjee was a gold medalist civil engineer who was credited with building the Lahore Post Office and Lahore Museum, alongside the famous architect Sir Ganga Ram. At the turn of the century, he drew from his engineering background to further develop Rajo Villa. He designed a second storey and added several Indo-Saracenic architectural details to the home, such as parapets, gothic style rain downspouts, and arches with voussoirs amongst others.

Over time, the home grew bigger and even in the context of the early 20th century, it was considered to be of palatial size for a family. Rajo Villa included a medical clinic and printing press (The Royal Medical Hall), as well as stables, quarters for domestic help, and additional kitchens. The built-on second storey featured a grand ballroom with a 20-foot ceiling, additional rooms which opened out onto terraces, and a rooftop third level with views of the bazaar.

It was also noted in the architectural study that nearly every living space had a fireplace, which is attributed to the Bengali family adjusting to Northern Indian winters. The front entrance along the main bazaar road is flanked by two brick pillars and a brick wall with decorative jali details, in addition to a marble front sign with ‘Rajo Villa’ inscribed into it. Art Deco additions were made in the mid-twentieth century, which included a stairway leading from the second story to the courtyard, along with courtyard gates.

Logue’s connection with Rajo Villa is entrenched in a poignant sense of nostalgia. “As a child, my visits to India were spent mostly in this house,” she says. “This was my foremost impression of my Bengali roots and family life in my father’s culture. After travelling across the world for 24 hours, and another four-hour drive in the family Ambassador, we would round the corner through the crowded bazaar to the front gates of Rajo Villa. An old historic home awaited me, filled with warm colourful walls, a radio playing Hindi music and smells of spices and bread in the tandoor. I have strong visual memories of the sabzi wallah bringing vegetables for dinner and the monkeys on the rooftop while we played nearby. It created a connection through all my senses, that a home away from home existed. I felt it deeply.”

It is easy to understand, then, how the home and the memories associated with it would have been instrumental in shaping Logue’s artistic practice. Rajo Villa has been her muse in a very tangible sense – a canvas that she uses to begin many of her creations. While the Indian-American artist visited Rajo Villa often in her childhood, she tells us how she wasn’t able to physically make a trip to the house for many years after that. “Through this time of absence I felt a deep yearning to be there,” she recalls. “I had dreams about the house and I started to paint and write inspired by the memories. In more recent years, I have finally been able to return. These visits were a transformative moment for me as an artist. On the anniversary of my grandmother’s death, I found myself staring into a space that lacked the normalcy of my childhood experiences. Gone was the bustling energy, the music playing and the family gathering. Instead of the family routines that I was used to, the house was now empty, devoid of the familiar ceremony. It was as if I needed the silence to feel the stirring in my soul.” Logue’s watercolour paintings capture an essence of the past that every Indian can relate to. They have the ability to conjure up personal memories for every individual viewer, pointing to a grand universality woven into tradition.

Even today, signs of the original bungalow built-in 1845 exist, and Rajo Villa stands as a unique synthesis of culture, regional style, and architecture.